The authors of antiquity and gladiatorial fights. The attitude of pagan and Christian thinkers

The attitude of emperors and Roman audiences to events such as gladiatorial combat is well known, but it is also worth noting the positions of ancient authors and writers. They came from different intellectual and cultural backgrounds, often representing a different world view.

The battles of gladiators and the problem of judging them was occupied by the minds of comprehensively educated people, namely intellectuals, philosophers, speakers, politicians, educators, theologians and clergymen who held the highest offices in the administration of the Roman state. Such people include Cicero, Epiktet, Seneca the Younger, Pliny the Younger, Emperor Mark Aurelius and a whole host of early Christian priests with Tertullian and Saint Augustine at the head. Due to their social position, they were in a way obliged to take a stand against the institutions of the gladiatorial games. Their opinions differed, and it should be noted that any contempt for these professions could have had a negative impact on the image of those who criticised them, especially during the early empire.

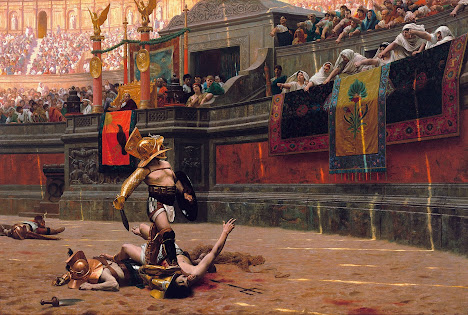

Initially, there were few condemnations, but it could not have been otherwise, as successive emperors were sitting in the grandstands as hosts of the spectacles and applauded from audiences of different social composition for the level of the Games. Shows in the amphitheatre were extremely popular and participation in them was treated as a civic duty to actively participate in the public life of the state. The grandstands were a veritable melting pot of human behaviour, where the excitement, fears, fascination and fears of Roman citizens were reflected. Empire society almost entirely accepted the brutality and cruelty of the gladiatorial games, demanding that they be organised more often in the first two centuries of the empire's existence.

The Romans treated demonstrations of combat as entertainment, a form of sport and a way of spending their free time, without thinking about the fate of the dying people and animals. It was extremely difficult to convince anyone of the destructive role played by such shows, and the imperial orders and decrees introduced over time did not help, nor did they reduce state spending on the Games. It was only the penetration of Greek philosophy into Rome and the development of Christianity that made human life more valuable. Criticism of the institution of the gladiatorial games was the result of a slow change of world view in intellectual and cultural circles, both Roman and Greek humanists. It is worth tracing the views of selected ancient thinkers, mainly those opposed to the bloody slaughter of people and animals.

Views on the usefulness of gladiatorial games have already been expressed at the end of the Republic. Cicero wrote of the few voices criticising the nature of the swordsmen's battles, while also wondering whether these opinions were correct. Arpinata made personal observations, from which a great deal of disgust and sadness is evident in the fact that people and animals are being killed to gain popularity among the popular masses.

In the Treaty of Duties, Arpinata divided the generous into the profligate and the noble. He included among the first to do so those who squander money on feasts, games, hunting and gladiatorial games. The noble ones include those who, among other things, buy out kidnapped family members from bandits or pay off friends' debts.

Despite the criticism of the Games, Cicero had no illusions about the actual significance of this phenomenon. He understood perfectly well the political and ideological background of the shows, which were ultimately supposed to bring popularity and support among the ruling circles. Arpinata showed an ambivalent attitude to swordsmen's demonstrations. The stoic philosophy, to which Cicero was faithful for the rest of his life, dictated the impassioned acceptance of pain, fear and awareness close to death. He believed that the death of a gladiator is in a sense worthy of the death of a philosopher who is aware that dying is a natural and inevitable process and affects every being. It may be that Arpinata exaggerated his assessment of how easy it is for gladiators to accept death in the arena, but his emotional approach to the problem under investigation is noteworthy. The whole phenomenon must have been the subject of a thorough analysis for him, since his reflections are so subjective.

It can be concluded that Cicero denied the rightness of organizing shows only for the pure satisfaction of the audience, without any connection with the practical dimension of gladiatorial combat. But when criminals fought, "there could not have been a better school, at least for the eyes, to teach how to despise pain and death. The preventive aim of the show was therefore justified for Arpinata. In addition, the speaker emphasised the bravery of the swordsmen, placing their youth as a model of physical endurance and courage. If a slave, a barbarian or a bandit endured pain bravely, a free Roman citizen had to do no other than that, and the differently-minded Romans compared Arpinata to screaming women, who react with lament to every pain and suffering.

He was the quickest and most profound criticism of the Seneca Games Younger, a stoic rhetor and philosopher and a teacher and advisor to Emperor Nero. The opinion of this outstanding intellectual was clear and unambiguous - unlike that of Cicero, who, as mentioned, expressed an ambivalent attitude towards wrestling shows. Seneca, in the spirit of Stoic philosophy, proclaimed the view that death should be considered according to rational categories. In his view, it is neither good nor bad, but is a natural process in the life of every human being. Even a sudden death was accepted by Seneca, provided that it occurred voluntarily. Gladiators in the arena certainly died a quick death and so did the author of these thoughts (forced to commit suicide by Nero). Seneca testified with his own life that man should be prepared to leave at any time, even when he enjoys a full life and has a high status in society.

Nero's counsellor was a skilled politician and he understood that in order to maintain public order in the state, it is good for "the villains to serve as a warning to all, and since they did not want to be useful during their lifetime, at least to benefit from their death". However, according to Seneca, the concept of utilitas (usefulness) did not include the shows he accidentally saw. Once he went to the show in the belief that he would see bloodless supplies, but he found himself fighting gladiators, which were brutal public executions. Seneca wrote to his friend Lucilius about these shows as a warning, highlighting the destructive role of the shows, which could deprave even the most enlightened people. In his account, he placed a fictitious spectator in the stands, with whom he conducted a dialogue among the passionate crowd.

For Seneca, the evil emanating from the crowd was a danger to every outsider and practically no one could defend themselves from the negative influence of the spectacles. He saw that in the audience, the system of values was completely different from that of the people who had not yet saturated themselves with the emotions that were beating from the arena. For these reasons, the philosopher appealed for people to stay away from the communities, especially during bloody performances. This was a way of protesting against the depravity of the human conscience by the gladiator games.

Seneca presented the problem of gladiatorial combat from a moral point of view, often comparing the bravery of swordsmen to the courage that every wise man should demonstrate. He stressed that if a convict is able to die with dignity, he would all the more wish for such an attitude from free and noble people. Unlike gladiators, wise men should not ask for mercy when death approaches - according to Seneca, the philosopher's attitude must be steadfast and steadfast at such a time.

Seneca's voice, which was a protest against inhumane events in the amphitheatres, reached only a small group of people and could not really change the nature of the Games, which were popular and cared for by successive emperors. However, the opposition expressed was an impulse for other thinkers and philosophers of the era to start further reflection on the sense of organising gladiatorial games.

The Epiktet of Hierapolis (from around 50 to 130 AD), a representative of the younger school of the Stoics, was a Friesian liberator who founded a philosophical school in Epira. He had a great influence on his contemporaries through his studies. He dealt mainly with ethics, criticising all Roman and Greek games. He was cool about gladiatorial fights, and, like Cicero, he believed that everyone should come to terms with the inevitable fact of death. According to him, people digest a constant fear of pain and death, and that is their real problem, not just a moment of suffering or dying. These views can be applied to the fighting gladiators, who have overcome fear while fighting in the arena.

Lukian of Samosata, a Greek rhetoric and satirist, was critical of the Games held in the East. In Ziva Demonaksa presented the rivalry between Athens and Corinth, as a result of which the Athenians, in order to increase their chances of winning, seriously considered introducing gladiatorial games. The widespread brutality and cruelty of the competition was the reason for a public speech by the philosopher Demonax, who called on the Athenians not to forget to demolish the Altar of Mercy before approving the project. Indeed, in the early empire, only the Greek intellectual elite had the courage to oppose the introduction of the gladiatorial games, as opposed to the common people who quickly accepted Roman entertainment.

Marcus Aurelius also averted gladiatorial fights, trying to reduce the frequency of their organisation. His activity was strongly influenced by the stoic philosophy to which he was faithful throughout his life. In Rozmyślanie ([To himself]) - a kind of a diary written in Greek - he presented a stoic-like reflection on the most important issues of life and death. The Emperor Thinking was aware of the transience and fragility of life, so he encouraged all reasonable Romans to devote themselves to faithful service to the state, cherishing the virtues and goodness, and even suggested seeking happiness in working for others. In the Marcus Aurelius value system, there was no room for perverse entertainment and play, which he contrasted with simplicity and peace of mind. He argued that death - which is something natural and inevitable in nature - should be treated with dignity and without fear. Anyone who did not understand this could only arouse pity by reminding them of their actions: "The jagged gladiators who fight wild animals, and although they are covered in wounds and blood, are asked to stop for the next day to be exposed to the same claws and fangs in the same condition".

According to the thinker, it is only through philosophy that one can know the true path to nobility and in order to achieve this state "one has to be similar to a wrestler, not to a gladiator. For when this sword, which he wields, throws - it dies, that one always has a hand and needs nothing else but to tighten it". For the Emperor, gladiatorial games were unworthy of the eyes and the soul, which is why he was one of the few Roman rulers who was able to subject them to consistent criticism, using Stoic ethics.

Another vote on the gladiatorial games came from Christian philosophers and theologians, who condemned the organisation of bloody demonstrations, especially during the period of temporary persecution. In order to understand the reason for the murder of the first Christian believers in the Roman amphitheatre arenas, we need to look at the testimonies of the era.

Christianity was founded in the first half of the first century A.D. in the Roman province of Judea as a result of the activities of Jesus of Nazareth (from 8/4 B.C. to 30/33 A.D.). After his death, the Christian teachings began to be preached by disciples (apostles), especially St. Peter (until around 67 AD) and a Roman citizen converted to Christianity, St. Paul of Tarsus (from around 5/10 to 64/67 AD). Thanks to the activity of the first missionaries, numerous Christian religious communities were quickly established. During the reign of Claudius, the new religion also reached Rome. This emperor was supposed to banish the Jews 'from Rome around 50 years ago for the fact that they constantly stormed, incited by some Chrestos'. Probably among the exiles were the first Roman Christians. Initially, their position in the Empire was not significantly different from that of Judaism and they were considered to be a Jewish sect at most. The Romans could not even distinguish between the two religions, and it was only the missionary activity of St Paul that showed the differences, which were quickly recognised. New believers began to arouse resentment or even jealousy among the local people who did not understand the exclusivity of Christ's religion.

In July 64 a huge fire broke out in Rome, which destroyed most of the residential buildings and numerous public buildings. Svetonius directly accused Nero of setting the city on fire, while Titus gave two possible reasons for this event: coincidence and the imperial order of Rome. The settlement of this issue remains an open question, although a coincidence is not ruled out, given that ancient cities have very often suffered such disasters. The emperor was suspected, however, of having become very unpopular.

He regarded the new religion as a 'fatal superstition'. (plea constantly repeated) and found them guilty. He stressed that they had not been proven, despite numerous interrogations, to be arsonists, but punished for their hatred of the human race, the Roman people. The state's attitude was mainly due to the difference in the new religion. Christians were faithful to the decalogue and did not recognise the Greek-Roman pantheon, which resulted in a refusal to worship the state gods. Secondly, Christians aroused aversion through the nature of the liturgy (for example, bread and wine into the body and blood of Jesus), around which many myths and superstitions (anthropophagia, ritual murders) grew. The preaching of the sermons on the coming of the Messiah and the final judgment also aroused consternation among the authorities and citizens of the Empire, who even accused new believers of imperialist intentions.

Public executions of convicts have been known since Augustus, but Nero has given them a new character through their scale and momentum. The first such serious and bloody persecution of Christians began to create a long list of victims - martyrs who died in circuses and amphitheatres throughout the Empire. Since then, the executions of Christians, along with other condemned convicts, have been carried out as part of Roman shows involving exotic predators. The punishment to which Christians were subject was called damnatio ad bestias (to devour the beasts) and was one of the most cruel and bestial forms of enforcement of Roman law. Only foreigners and other believers were subject to it, and it was the most disgraceful of punishments. Such executions were part of an integrated programme of demonstrations involving gladiators and beasts, with whom they together created a complete picture of Roman shows during the Empire era. Further persecution of Christians took place during the reign of Domitian and Marcus Aurelius. The latter were particularly acute when 48 Christians condemned to be eaten by wild animals died in one day in Lugdunum (177). Before the executions began, the names of the condemned were publicly mentioned in order to humiliate them even more, something that was not even practised in Rome.

In fact, however, in the first and second centuries AD, a relatively small number of Christians were accused and sentenced to death, due to the lack of a precise legal basis for determining the scale of the offence. The finding of guilt and the imposition of the death penalty were based more on a sense of the situation by individual governors and prosecutors in the Roman provinces. Their verdict was influenced by local communities which held demonstrations and violently demanded condemnation of all those suspected of Christianity. In order to maintain public order in cities, the authorities most often listened to reports and sentenced people to death. The activities of Christian communities in the east were met by, among others, Pliny the Younger (Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, from around 61 to 113), who, as governor of Bithynia, was unable to take a clear position on this problem. The Trajan, who was in power at the time, treated the subject in general terms, acknowledging the guilt of those who refused to make sacrifices to the national gods.

Bishop Antioch Ignacy (from about 30 to 110 AD) has seen the volatility of society's moods. Around 110, he and a group of his companions were sentenced to be torn apart by wild animals.

Some educated Christians wanted martyrdom like Ignacy Antioch. Examples are: St. Polycarp (died in 155 or 156), Bishop of Smyrna, who was originally to be thrown to the beasts and eventually burned, and St. Felicia and Perpetua, who according to tradition had to be struck by gladiators with a sword because the wild beasts were afraid of them (around 203). The martyrs themselves therefore asked to die in the name of Christ, rejecting all help. These were acts of zealous faith, which, however, were clashing with religious fanaticism. In time, even the Church banned provocative behaviour that irritated local authorities and damaged the image of the entire Christian community.

The vast majority of the pious followers of Christ avoided conflicts with the local authorities in view of their lives. During the early empire, the Roman state was unable to fully develop uniform legislation with regard to Christian communities, and it was only in the third and early fourth centuries that anti-Christian laws were introduced.

At the beginning of the third century, the Christian theologian Tertullian spoke with harsh criticism of the gladiatorial games. He was aware that the swordsmen's shows and performances were linked to religious tradition and ritual, but he criticised the form and manner of worshiping the gods and the dead. In Tertullian's worldview, the programme of gladiatorial games could not be accepted because of their idolatrous character. According to the theologian, it was determined by their genesis, nomenclature, splendour of the setting and place and technique of organisation (circus or amphitheatre. Every Christian should renounce these entertainments in order to protect himself from losing his peace of mind and moral purity.

Unlike Cicero, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, Tertullian was opposed to justice being given to convicts in the arena. He believed that this type of death was disgraceful and unworthy of the human person, as evidenced by his admonition that 'an honest man must not enjoy the torment of his neighbour; rather, he should regret that a man his equal has become a villain, that he is so cruelly killed'.

Living more than a century and a half later, Saint Augustine wrote about the negative impact of the gladiatorial games on the awareness of young and intelligent people.

In his Confessions, Saint Augustine presented an interesting psychological study of a young man who, under the influence of the behaviour of the audience, was incredibly quickly spoiled and morally demoralized. Although the description comes from the end of the fourth century, we can assume with a high degree of probability that the type and scale of emotions during gladiatorial fights was similar to that at the end of the second century. The information about Ellivius is one element which makes it possible to confront two world views: Christian and pagan. Saint Augustine presents the influence of the Games on the breakdown of values in the mind of every human being, which can be seen thanks to Christian doctrine. This is contrasted with the attitude of the pagan world created by the players and the audience, who accept the whole show uncritically.

However, in the end, Ellius converted to the previously chosen path, which was a harbinger of the future triumph of Christianity over the pagan (Roman) world, which was leaning towards collapse. It is worth noting that Bishop Hippo's philosophical deliberations are universal in nature and have not lost their relevance to this day because they concern questions about the nature of the human psyche.

***

Over the centuries, many myths and stereotypes have grown around the problem under examination, which have largely obscured the real role and importance of the institutions of the gladiatorial games. We should agree with the fact that the form of the phenomenon under investigation has actually taken on the character of bloody slaughterhouses, which have blended into the everyday landscape of ancient Rome. They were criticised by Seneca the Younger, Epiktet and partly Cicero, among others, while Marcus Aurelius did not accept the gladiatorial fights themselves, but he did not hesitate to send Christians to suffer in the amphitheatres, because the followers of Christianity were considered to be a group that undermined the authority of the imperial authority, and thus of himself.

For a long time, dissenting voices of dissent were being spread in the everyday imperial reality, which included the struggle for power and the people's favouritism of the ruling elite. This does not mean, however, that Roman civilisation was experiencing a decline in culture and science - on the contrary, during the reign of the first three imperial dynasties, the Empire enjoyed previously unknown internal peace and economic stability, and the Games took on the character of spectacular spectacles that legitimised the rule of successive emperors.

Christian culture, through the work of its first theologians and philosophers, has essentially consolidated the one-sided and largely superficial image of the institution of gladiatorial games. The destructive role of the spectacles was already recognised by the aforementioned writers and politicians. For people like Tertullian and Saint Augustine, the Games were an insane and idolatrous phenomenon, feeding on the blood of innocent people. Early Christian scholars were often unable to go beyond their worldview and their messages obliterated the basic political and social aims of gladiatorial performances. For this reason, a historian - who writes in hindsight and has the appropriate source knowledge - is forced to approach Christian writings with caution and confront them closely with earlier messages from pagan writers. Then - albeit only in part - we will get a fuller picture of the issue which still fascinates the world of science and beyond today.

Comments

Post a Comment